Scientist Uncovers the Truth About Lying

A lifetime of groundbreaking research done by behavioral scientist Dan Ariely has finally shed light on why people lie, and the implications it has on our society and our economy. Through a simple experiment, done thousands of times with thousands of participants, Professor Ariely has uncovered numerous universal truths about lying, six of which we have shared below, and all of which can be seen in his documentary (Dis)Honesty. In a fascinating reveal, he goes a step further and shares the fool-proof, simple trick he discovered that stops lying in its tracks.

Professor Ariely’s experiment is a simple one called “The Matrix Experiment.” Participants are given a packet of math problems and a small amount of time in which to do them. When the time is up, they count how many they got correct. They then bring their test packet up front, shred it in a shredder, and tell the test administrator how many problems they got right. For every problem they say they answered correctly, the administrator gives them $1.

The twist? The shredder has been tampered with by Ariely’s team, and it doesn’t actually shred the test packet. So, after the participants leave, they can easily tell who lied and by what degree. Through replicating this test thousands of times and in countries all over the world, Ariely and his team was able to uncover what variables cause people to be dishonest.

1. It is not the big lies that impact society, it is the little ones.

Ariely’s team discovered that of the 40,000+ people who have participated in the Matrix Experiment, nearly 70% cheated. Of those, about 20 were what he called “big cheaters.” They claimed they solved all 20 problems, and collectively they stole $400 from the study team. About 28,000 people, on the other hand, were what he called ‘little cheaters,” who falsely upped their count by maybe one or two problems. These people collectively stole $50,000 dollars from the study. Ariely extrapolates this to society as a whole, saying that “big cheaters are rare, and because of that their impact on society is relatively low. But we have a ton of little cheaters, and because there are so many of us, the economic impact of that is actually incredibly high.”

2. The more we lie, the easier it gets.

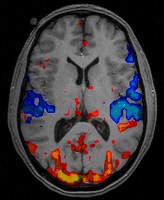

By studying what happens to the brain when people lie, Ariely’s colleagues were able to see that when people first tell a lie, there is a huge response in their amygdala, insula, and other areas involved with emotion.

However, after ten lies, these areas of the brain stop lighting up. The emotional and physiological impact of the lies we tell stops registering; and this is how lies often can grow beyond our control.

3. When people in our social circle lie, we lie more.

In one version of the experiment done with students from the same college, Professor Ariely’s team hired an acting student, who thirty seconds into the experiment said they solved every problem–clearly impossible–went up to the front, and received $20 from the study administrator without issue. The result? Many more of the remaining participants cheated.

However, when the team dressed the actor up as a student from a rival college, and had him again blatantly cheat and get away with it, the rate of cheating actually went down. This proved that the cheating wasn’t about the probability of getting caught, but rather about what people felt was socially acceptable.

4. Lying is essential for humans.

Studies have shown that all animals lie, and that the bigger the brain, the larger the capacity to lie. For humans, this is in certain cases a good thing. For example, it has now been shown that a child’s ability to lie and imagine things that aren’t true actually builds their brain. It develops the “theory of mind,” which is how we imagine and understand what the people around us are feeling. Through lying, children are actually developing the capacity to understand that others have different thoughts and beliefs from their own, and to predict or imagine what they might be.

5. Men and women lie the same amount.

It’s true! Rates do not change across genders. Professor Ariely also discovered that no country is more honest than any other–despite administering exams in dozens of countries, such as the the UK, Colombia, Greece, Canada, and South Africa, no noticeable difference in cheating rates occurred.

So how do we curb lying?

6. When people recall any moral code, no matter what it is, they don’t cheat.

The most surprising result of the matrix test occurred when Ariely and his colleagues tested the effects of recalling moral and honor codes on matrix participants. People, including self-identified atheists, were asked to recall the Ten Commandments immediately before taking the test; not one person could list all of them, but not one person cheated. The results did not vary depending on how many of the commandments people remembered, or what religion they were–no one cheated. Just being reminded was enough.

It was the same with non-religious moral codes. Students at one university that did not have an honor code took the test and cheated. When students from the same school were asked to sign a pretend slip of paper stating that they understood the honor code, and then take the test, no one cheated. Students at a university that had a well-known honor code–sang at all rallies and sports games–cheated the same amount as students at the school without an honor code; that is, until they were asked to recite their honor code before taking the test. In that experiment, no one cheated.

Ariely’s take away? To change people’s behavior, we don’t have to make sweeping changes to society or culture, but rather remind people in small ways of their own moral fiber. What if government workers began each day saying, “I was elected by people who trusted me, and I want to do what is best for them”? What if financial advisors began each day saying, “People have trusted me with their money, and my decisions will effect their families and their livelihood”?

All of us could use a moment each day to reconnect to our moral compass. To learn that science now shows that this one moment is all it takes to prevent dishonesty, is truly uplifting.

And the best news of all? The documentary is now available for streaming on Netflix.