From the Archives: The Original Review of ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’

This review of the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” ran on June 18, 1967, with the headline “We Still Need the Beatles, but …” The Times’ current chief pop critic, Jon Pareles, revisited the album on its 50th anniversary this week.

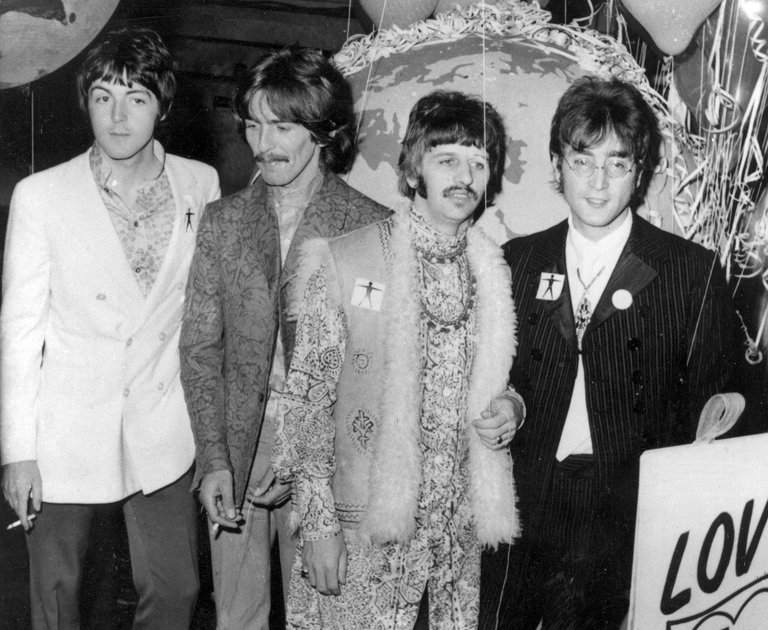

The Beatles spent an unprecedented four months and $100,000 on their new album, “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band” (Capitol SMAS 2653, mono and stereo). Like fathers-to-be, they kept a close watch on each stage of its gestation. For they are no longer merely superstars. Hailed as progenitors of a Pop avant garde, they have been idolized as the most creative members of their generation. The pressure to create an album that is complex, profound and innovative must have been staggering. So they retired to the electric sanctity of their recording studio, dispensing with their adoring audience, and the shrieking inspiration it can provide.

The finished product reached the record racks last week; the Beatles had supervised even the album cover — a mind-blowing collage of famous and obscure people, plants and artifacts. The 12 new compositions in the album are as elaborately conceived as the cover. The sound is a pastiche of dissonance and lushness. The mood is mellow, even nostalgic. But, like the cover, the over-all effect is busy, hip and cluttered.

Like an over-attended child “Sergeant Pepper” is spoiled. It reeks of horns and harps, harmonica quartets, assorted animal noises and a 91-piece orchestra. On at least one cut, the Beatles are not heard at all instrumentally. Sometimes this elaborate musical propwork succeeds in projecting mood. The “Sergeant Pepper” theme is brassy and vaudevillian. “She’s Leaving Home,” a melodramatic domestic saga, flows on a cloud of heavenly strings. And, in what is becoming a Beatle tradition, George Harrlson unveils his latest excursion into curry and karma, to the saucy accompaniment of three tambouras, a dilruba, a tabla, a sitar, a table harp, three cellos and eight violins.

Harrison’s song, “Within You and Without You,” is a good place to begin dissecting “Sergeant Pepper.” Though it is among the strongest cuts, its flaws are distressingly typical of the album as a whole. Compared with “Love You To” (Harrison’s contribution to “Revolver”), this melody shows an expanded consciousness of Indian ragas. Harrison’s voice, hovering midway between song and prayer chant, oozes over the melody like melted cheese. On sitar and tamboura, he achieves a remarkable Pop synthesis. Because his raga motifs are not mere embellishments but are imbedded into the very structure of the song, “Within You and Without You” appears seamless. It stretches, but fits.

What a pity, then, that Harrison’s lyrics are dismal and dull. “Love You To” exploded with a passionate sutra quality, but “Within You and Without You” resurrects the very cliches the Beatles helped bury: “With our love/We could save the world/If they only knew.” All the minor scales in the Orient wouldn’t make “Within You and Without You” profound.

The obsession with production, coupled with a surprising shoddiness in composition, permeates the entire album. There is nothing beautiful on “Sergeant Pepper.” Nothing is real and there is nothing to get hung about. The Lennon raunchiness has become mere caprice in “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite.” Paul McCartney’s soaring Pop magnificats have become merely politely profound. “She’s Leaving Home” preserves all the orchestrated grandeur of “Eleanor Rigby,” but its framework is emaciated. This tale of a provincial lass who walks out on a repressed home life, leaving parents sobbing in her wake, is simply no match for those stately, swirling strings. Where “Eleanor Rigby” compressed tragedy into poignant detail, “She’s Leaving Home” is uninspired narrative, and nothing more. By the third depressing hearing, it begins to sound like an immense put-on.

There certainly are elements of burlesque in a composition like “When I’m 64,” which poses the crucial question: “Will you still need me/Will you still feed me/when I’m 64?” But…

Comments